I’ve been following @gocarriesew as she works her way through the Top Down Center Out method with the peppermint wide leg pants. Recently she shared how there are so many decisions one has to make while fitting, each choice creating a different path on the road to a successful garment. It can feel overwhelming, especially in the beginning. Learning how to navigate the decision making process is an essential part of fitting, yet this skill is rarely discussed.

Seeing how other people make fitting decisions is always a learning opportunity for me. So in the spirit of sharing, this post will be a little different than usual; I’ll take you along with me as I fit the tester version of the Coe trousers, and I’ll highlight the decisions that I made and why I made them. If you’re looking for the full review of the pattern, see my previous post on the Coe trousers.

Evaluating the Toile

I used the Top Down Center Out (TDCO) method from Ruth Collins to fit these trousers. It’s the only method that allows me to explore different fitting choices and problem solve with a single toile. If you’re new here, I have a whole slew of videos if you want to learn more, or head to Ruth’s Instagram or her Threads article.

One leg or two?

When I use TDCO, I usually make a one-legged toile because it’s fast, efficient, and the best way to visualize the crotch fit. However, there are some situations when a two-legged toile is called for. I decided to make a two-legged toile for my Coe pattern test so the designer could get the full, bifurcated visual of how the trousers fit.

I also sewed the entire zipper fly on my toile, rather than pinning the fly closed or omitting the fly. Constructing the full zippered closure in the toile gives a smoother center front and a more accurate fit through the torso.

Fabric choice for the toile

I’m using cotton muslin (aka calico) in these fitting sessions. Every time I use this fabric to fit a trouser toile, I’m reminded of what a poor substrate it is for fitting, second only to tissue paper (sorry not sorry, Palmer and Pletsch).

Fabric choice affects fit, so the best fabric for the toile is one that’s closest to my final garment fabric in weight and drape. Cotton muslin is too lightweight for making trousers, with little drape or give. It shows every little wrinkle and fold, whereas most bottom weight fabrics won’t. It’s possible to spend days or weeks chasing down perceived fit issues in cotton muslin that completely disappear in a different fabric. Unfortunately, muslin was all I had on hand, so I had to make it work.

Fitting the waistband

My measurements are 32″ waist and 42″ hip, which put me in a straight size 12 for this pattern. I made the waistband to check the fit, and happily I needed no modifications (a first!). The waistband has a little less than an inch (2.5cm) of positive ease, which makes for a very comfortable fit.

Fitting the toile: Top down

Next, I tried on the toile. The Coe trouser instructions tell us that the intended vertical ease between the crotch or “saddle” of the trousers and the body should be 1/2 inch. I’m 4 inches taller than the pattern is designed for, so I knew I would need to add length to the rise.

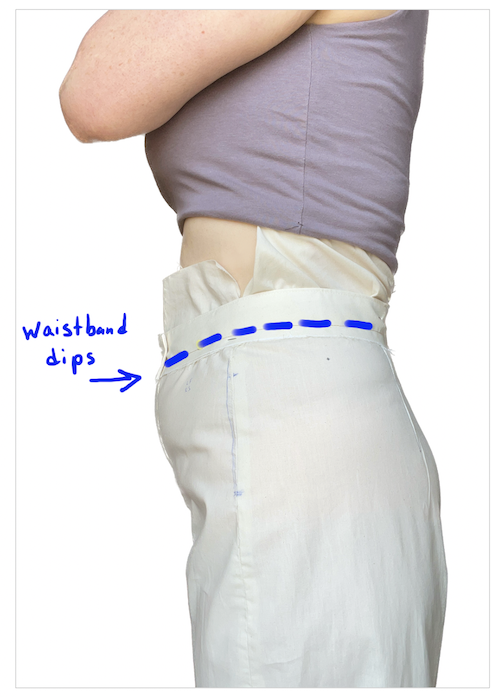

It’s not recommended to start fitting with the toile pinned to the waistband as drafted, but for the sake of comparison, here is what the toile looks like with no adjustments in the rise:

While the front view looks fine, the crotch seam is uncomfortably tight against my body, and the waistband is pitched forward. In the back, I’ve got a bad case of “hungry bum”.

Using TDCO, I lengthened the vertical rise evenly all the way around the toile until I hit the intended half inch sweet spot for crotch ease. Then I added a little extra length just in the front rise to get the waistband to be more level.

In the photo above, I’ve added 1 inch in vertical length to the front rise and 1/2 inch to the back rise, and I’m happy with the results. Yes, I have a small fold of fabric that’s pointing to my knee on the right side of the back view. I often see this when I’m using cotton muslin to toile, and it’s probably due to body asymmetry. I did no additional adjustments to get rid of it, and it disappeared in my final garments.

So the length adjustment alone is enough to get me to a good fit, especially in the back:

Fitting the toile: Center Out

Next, TDCO directs us to work from the center out. Often, I need to adjust how the leg hangs on my body by moving the side seam up or down at the waistline. I use the hem as my visual cue for whether the leg hangs straight; in this case the toile didn’t need any adjusting here.

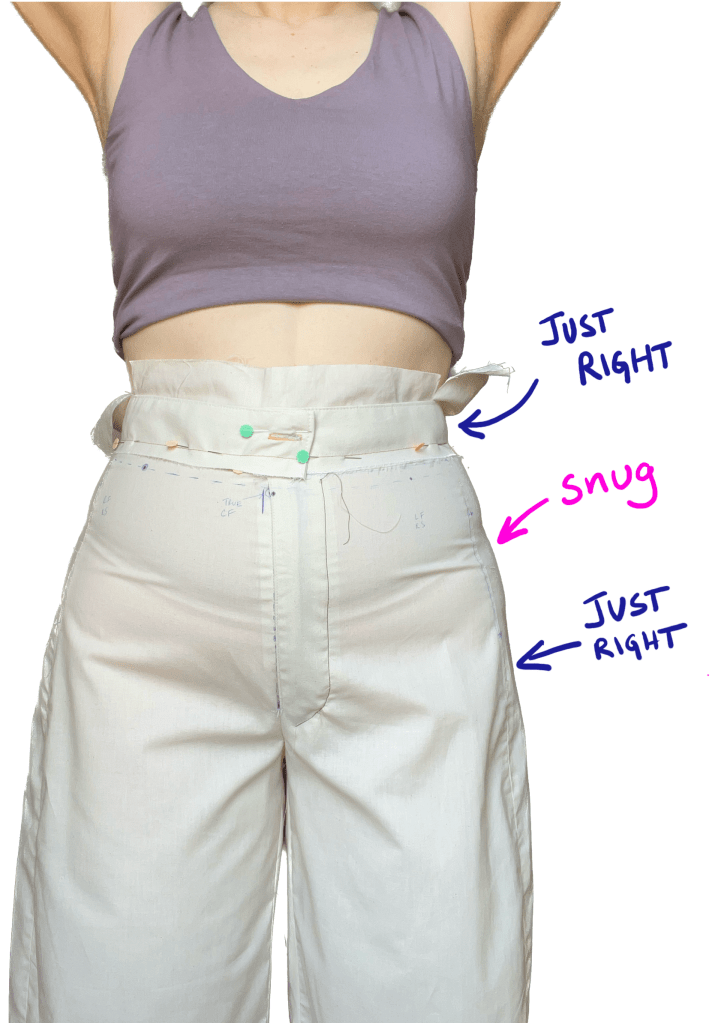

Then I assessed the circumference of the toile. I had already established that the waistband circumference felt great, so I worked my way down the body. The hip circumference on the size 12 gives me about 2.5 inches of ease. It’s close-fitting without being restrictive to walking or sitting. The thigh and leg ease is also quite generous, so no changes are needed.

The high hip (in pink, above right) is the only place that felt quite snug. The muslin is tight over my abdomen, and I have zero or even a little negative ease here. You can also see the fabric is straining with some horizontal wrinkles.

I omitted the pockets on this toile for simplicity, but if I had included them, they would be right where the trousers are tightest. That’s an invitation for a gaping pocket. Some folks don’t mind a little gapping–it’s a judgement call for each maker whether this is bothersome, but I’d prefer a little more ease and a flatter pocket.

So to address the high hip circumference and pockets, I have a number of options for how to proceed.

Option 1: Let out the side seam

Typically with TDCO, if the circumference of the toile needs adjusting, we let out the side seam using the extra fabric in the seam allowance. So I could add fabric to the front and/or back pieces to add ease and then blend down the hip.

As an experiment, I seam ripped a few inches of the side seams on my toile to see what it would look like.

The seam naturally wanted to splay open about a half inch per side (1 inch in total circumference). My first impulse was to add about 1/4″ to the seam allowance on the front and back side seam at high hip, like this:

But wait! This modification would have some important consequences due to Coe’s pocket design. Making the seam more curved at high hip would mean making the pocket opening more curved, as well. The resulting front piece looks a little strange (below); that curved pocket opening might act like a flap and stand away from the body, rather than lie flat. Not ideal.

The better option here would be to size up in the hip, blending the extra fabric needed at high hip with a larger circumference in the true hip.

But the trade-off here is that I would add more ease at the hip and thigh for an overall looser fit through the torso. Sometimes this can be a great strategy when fitting, but I wanted to see if there was another solution that preserved the original hip and thigh circumference of the size 12.

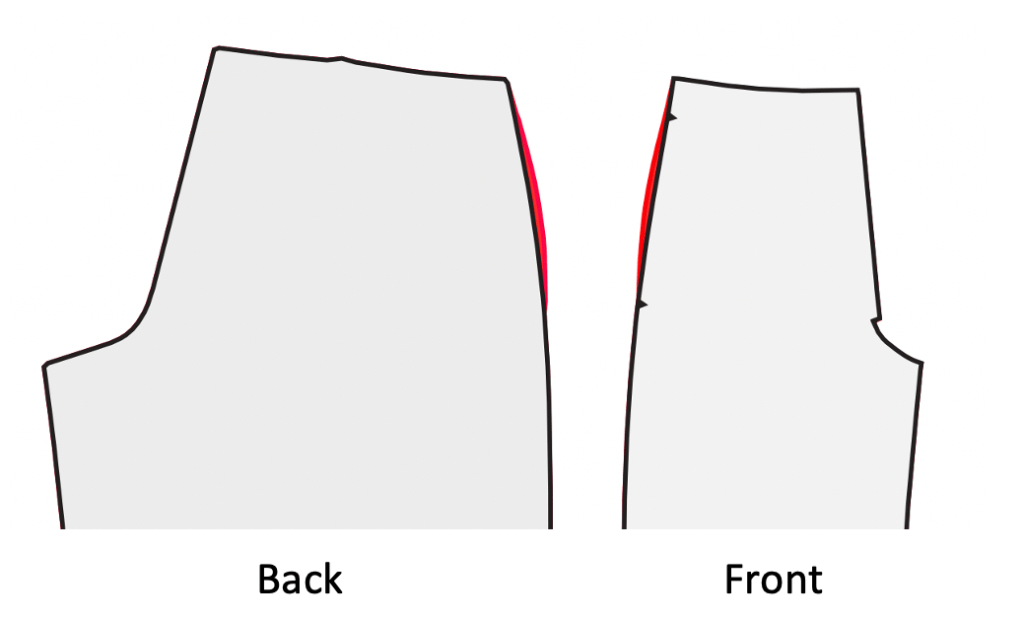

Option 2: Curve the back dart

To give myself extra room at the high hip level, an alternative would be to leave the side seam and pocket opening alone and look to the back piece instead. The back dart is an attractive option, since it’s ideally positioned around high hip level.

I could curve the back dart (below, pink), reducing the dart intake at the high hip level but maintaining the same intake at the waist. This approach could give me back a quarter inch on each side of the dart, which translates to an additional inch of fabric across the entire back piece right around high hip level.

Option 3: Alternative construction techniques

Construction techniques affect fit, and there are a variety of methods to stabilize a gaping pocket.

Pockets gape because the cut edge is slightly on bias, and because they are required to curve around the body and stretch out as we move. One solution is to fuse the wrong side of both the outer and inner edges of the pocket opening with interfacing, or use a strip of twill tape or a piece of selvedge sewn along the inside of the pocket opening. The pocket opening can also be cut 2-3mm shorter than the piece it lays on top of, sort of like negative ease for your pocket opening.

A pocket stay is another common solution found in many trousers with on-seam pockets, and there are a variety of ways to construct a stay (for example, here and here). In some cases, a short length of petersham/grosgrain ribbon is used to secure the pockets to the center front seams (as illustrated below), or the entire pocket can be extended to create the stay.

While a pocket stay wouldn’t give me any more room at high hip, it would help to control the front pocket from gaping open and give me a more “secure” feel to the front of the trousers. I bookmarked this idea as I continued to mull over other potential solutions.

Option 4: Fabric choice.

Like construction techniques, fabric choice also affects the fit. As I mentioned above, the cotton muslin (aka calico) that I used for the toile has very little give or drape. Low or negative ease around the abdomen can be intentional in a close-fitting design, and it’s likely that my final fabric would relax and loosen after a few wears, especially if I chose my fabric wisely. A linen or a cotton twill will usually grow as it breaks in, so the easiest solution could be to switch fabrics.

Coe Trousers, Version 1: Linen

I opted for the fewest number of adjustments possible for my first pair of Coe trousers. So I made length adjustments only, adding 1 inch to the front rise, 1/2 inch to the back rise, and 2 inches to the leg. I deliberately chose a 6 oz linen to test Option #5: would switching fabrics resolve my fit issue?

If you read my previous post, you’ll know that these linen trousers turned out well. They are comfortable and very wearable. The high hip is no longer tight like it was in the toile, so the linen has grown a bit as anticipated.

However, the front pockets gape a little and the side seam is pulling toward the back slightly on my right side (hello again, body asymmetry). So I wanted to try a different solution.

Coe Trousers, Version 2: denim

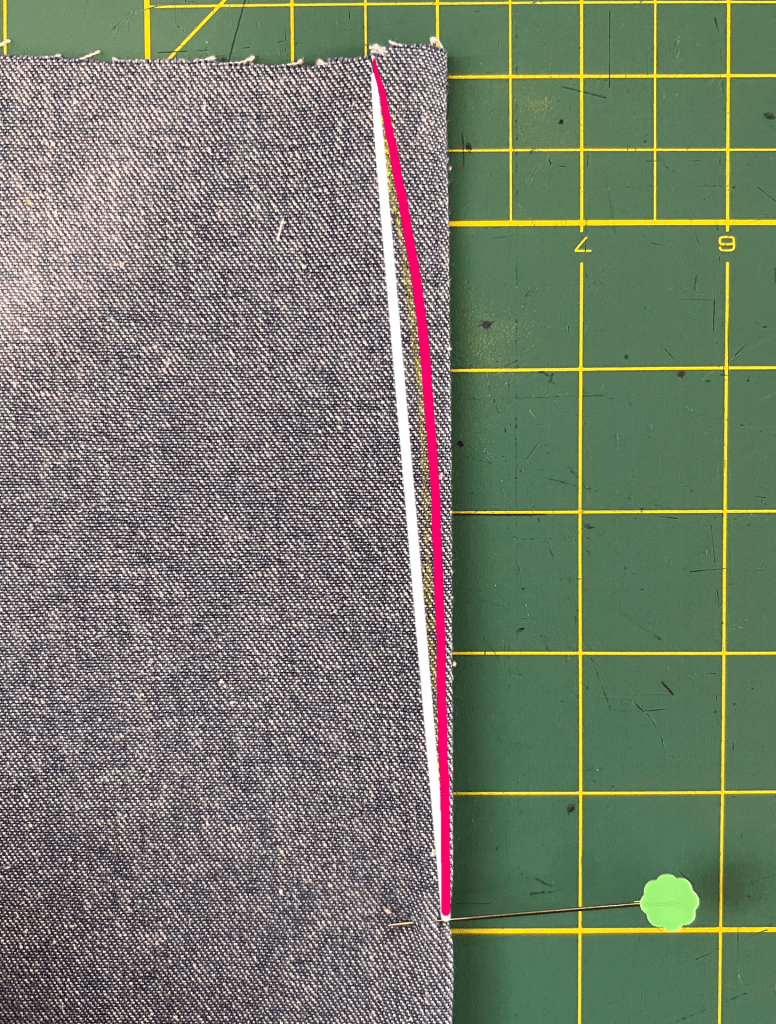

For my second pair, I switched fabrics to an 8oz cotton denim. Twill fabric will also relax and grow with wear like the linen, but I wanted to try some additional tweaks to resolve the pocket gaping.

For this pair, I chose a combination of Option 2 and Option 3. I curved the back darts to add ease at high hip and added a pocket stay. I think the results speak for themselves:

Final thoughts

All in all, my final edits to the flat pattern were minimal, thanks to Daughter Judy’s drafting and TDCO:

Decision making while fitting can feel overwhelming at times. Between pattern adjustments, construction, and fabric choice, there is a lot to consider. I don’t usually know what changes that I’ll need when I start out with a new project. That uncertainty can feel uncomfortable.

With practice and patience, I’ve been able to develop more of an intuition for what to try and a higher tolerance for the uncomfortable stage in the middle of the fitting process. I’ve also learned to trust that the TDCO workflow will get me to a successful fit even if I can’t always see exactly where it’s leading me at first.

Of course, I’m still learning as I go, too–that’s the fun part! I’ve got a few more TDCO fitting deep dives coming up, so stay tuned if this post was helpful.

Leave a reply to Emma Cancel reply